Jim Rugg talks about several of his works, life as a creator, and gives in-depth answers about Afrodisiac and Street Angel.

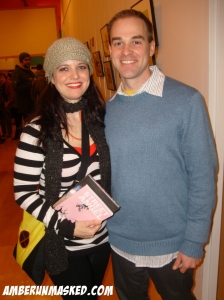

I got the pleasure to meet Jim Rugg and Brian Maruca at the Toonseum in Pittsburgh, PA for an exclusive launch party celebrating the Afrodisiac book based on a sexy heroic character in a blaxploitation setting.

I got the pleasure to meet Jim Rugg and Brian Maruca at the Toonseum in Pittsburgh, PA for an exclusive launch party celebrating the Afrodisiac book based on a sexy heroic character in a blaxploitation setting.

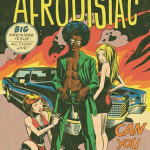

AFRODISIAC

AL: Do you feel that there are sensitivity issues being two white guys that wrote and illustrated a blaxploitation novel?

JR: No. Would there be sensitivity issues if an African-American team of creators wrote and illustrated a comic that featured white people? Are there sensitivity issues concerning two guys writing and illustrating a comic with a female lead (“Street Angel)”? Or with a couple of middle-aged people writing and illustrating a comic about a teenager?

In my opinion, “Afrodisiac” is about the blaxploitation genre of the 1970s. It’s not meant to be a statement or comment on African American culture, and I think that is obvious to anyone who reads the book. Depending on the treatment of the material, I think it could be a sensitive issue, but in the case of “Afrodisiac,” I don’t think it is.

AL: Who would win in a fight: Afrodisiac or Shaft?

JR: In a street fight, Afrodisiac can’t lose.

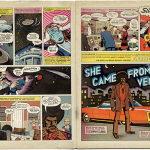

AL: In the book, you don’t always have continuous stories. Some pages are just covers or tear sheets eluding to the adventures of Afrodisiac. Why did you take that approach rather than just telling a linear tale?

AL: In the book, you don’t always have continuous stories. Some pages are just covers or tear sheets eluding to the adventures of Afrodisiac. Why did you take that approach rather than just telling a linear tale?

JR: I’m interested in trying different storytelling techniques. I went through a phase where I was watching a lot of exploitation movie trailers, and I tried to decipher the truncated storytelling techniques that were used to cut those trailers. During the same period I became interested in how Chip Kidd was building narrative by recontextualizing old comics (specifically the sequence in the back of the “Plastic Man” book he did with Art Spiegelman). Towards the end of the book’s assembly, I began thinking about the way different devices re-format content and how that affects the original material.

The whole thing with comics is sort of like film editing. It relies on the juxtaposition of two different images/moments/cues to create meaning. “Afrodisiac’s” format reflects my interest in this relationship between context and meaning. The internet has taken this recontextualization to such heights that one could argue it’s supplanted the artist’s original intentions. Think about how many comics, movies, books, songs, etc. that you encounter exclusively online, out of the context they were originally arranged or intended to be seen, heard, read, etc. I am aware of far more comics now through excerpts and individually reproduced panels than I am the actual comics. It’s not a new phenomenon, but it has grown exponentially in the last 15 years. The rearrangement of content by the reader or the re-editing and representation of content by users is something that hasn’t been widely addressed by most creators. By using tears sheets, excerpts, covers, etc., I think it makes the book more friendly to people who may encounter it outside of the book and the arrangement we created within the book. This is something that happens with larger characters frequently. For example, “Batman” – some people think of “Batman” as the 60s camp, pop icon, others may think of him as the Neal Adams or Frank Miller creature of the night, still others imagine him as Bruce Timm’s animated adventurer. It’s all based on the context in which individuals encounter the material. We wanted Afrodisiac to feel like a fictitious character, and using parts of stories and covers and individual panels along with various length stories, was how we tried to accomplish that.

AL: Besides getting bitten by a radioactive bug, Afrodisiac seems to have several origins. Why did you pick one and build from there?

AL: Besides getting bitten by a radioactive bug, Afrodisiac seems to have several origins. Why did you pick one and build from there?

JR: I love the ridiculous origins of old comics and I hate the way comics of the last 20 years waste time over-analyzing those silly origins. So we did different origins because they are awesome. And we avoided focusing on one origin because that stuff almost always sucks (except “Batman: Year One” and Barry Windsor Smith’s “Weapon X”).

AL: You easily included President Nixon in the story as many Presidents have in comics. Do you think the appearances of President Obama actually added to their stories or were they just commercial hype?

JR: Including President Obama in comics is just hype to sell comics, except perhaps the Savage Dragon’s early endorsement of Senator Obama when he was just a Presidential Candidate. I think that was more of an expression of Erik Larsen’s politics rather than a blatant attempt to capitalize on President Obama’s celebrity.

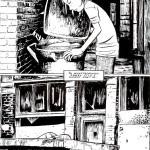

STREET ANGEL

AL: In Street Angel, you created a character with some similarities to Buffy the Vampire Slayer – not only with bad ass moves but also her attitude and giving the book a serious overtone that looms over the fun, in your case homelessness. You have less than six degrees from Joss Whedon anyway with your new work on The Guild comic. Was Buffy an influence?

AL: In Street Angel, you created a character with some similarities to Buffy the Vampire Slayer – not only with bad ass moves but also her attitude and giving the book a serious overtone that looms over the fun, in your case homelessness. You have less than six degrees from Joss Whedon anyway with your new work on The Guild comic. Was Buffy an influence?

JR: My work is even closer to Joss Whedon than “The Guild.” I did a comic for “Dr. Horrible” before I started “The Guild.” Go, Joss!

I had never watched an entire episode of “Buffy” until we completed “Street Angel.” Although I did see the movie in the theater! After we finished “Street Angel,” I picked up the DVDs, and I love “Buffy!” Love it. It’s been on Logo lately, and it’s so good!

AL: Can you reveal the real backstory to Street Angel and explain why she’s on her own and homeless or will that spoil the book?

AL: Can you reveal the real backstory to Street Angel and explain why she’s on her own and homeless or will that spoil the book?

JR: Remember when Wolverine was awesome? You know, before they revealed his origin?

AL: Will Street Angel’s story ever be continued?

JR: Hopefully. We have another volume kind of figured out. But we’d have to spend a lot of time that I don’t have right now. We’ll see. Assuming the world doesn’t end and Brian and I don’t die prematurely, I think there will be more.

AL: What’s One Model Nation about?

AL: What’s One Model Nation about?

JR: It’s about an influential, but little known band from Berlin in the 1970s that unwittingly becomes the soundtrack for a terrorist movement that has infiltrated the youth culture – the Baader-Meinhof Gang. The book deals with the trouble the band gets in and their struggle to create art and to avoid politics and how those two things might not be possible. I think it’d be accurate to call it historical pop fiction because many of the events and characters in the book are either based on or inspired by true events.

AL: Do you have a favorite convention experience?

JR: I was on a panel with Jaime Hernandez at HeroesCon two years ago. That was amazing.

The first time I ever exhibited at a show, I ended up in an aisle with Playboy Playmates, B-movie scream queens, and strippers or hookers or something (there was a weird hierarchy in the aisle in terms of the women and their claims to fame). Next to me sat a Playmate from the 90s (this was in 2000, so that made more sense), next to her was a Playmate from the 80s, and next to her was a Playmate from 70s. Monday after the show, I realized the Playmate from the 70s was the Playmate that appears in Centerfold form in Chester Brown’s I Never Liked You, which is one of my all-time favorite comics. I kick myself for not getting her to sign that page and then sending it to Chester. That was a weird show, and since it was my first one, I didn’t realize just how strange it all was until years later.

AL: Will fans ever get to see a costumer as Afrodisiac at your booth surrounded by hot babes?

JR: I doubt it.

AL: A lot of fans imagine doing exactly what you are but they don’t know where to begin. What sort of schedule to keep?

JR: I get up at 6 each day, drink coffee, see the wife off to school, and then work until it’s time to make dinner (with a small lunch break in the middle and perhaps a run). Depending on how busy the schedule is, sometimes I’ll work in the evening till 9 or 10 (I try not to do this), and sometimes I’ll get up earlier like 4:30 or 5.

Weekends…I usually work a little bit on weekends but try to spend time with family and friends if possible.

It’s a weird thing, because before I did this for a living, I had a day job and would draw in the evenings and weekends for fun. Now, it’s hard to stop working because for the most part I love doing it. But I don’t think it’s healthy to work too much or to focus too much on one thing. I’m still trying to figure out that balance.

AL: Do you get writer’s block or start projects that that you just can’t seem to finish?

JR: Absolutely. It’s unpleasant. The writer’s block is terrible, and the few times I’ve really had it, I’m not sure what makes it go away. I think it’s easier to come up with half a dozen ideas than one. So I tend to multi-task (it’s also a necessity as a freelancer). Often, if I’m dealing with writer’s block, I’ll spend more time on an art assignment, which is a nice option.

Starting something and not finishing it isn’t something I’ve had too much trouble with so far.

AL: Has your family always been supportive of your comic work or did you have to convince them that there are ways to make it in this industry?

JR: It was very important to my family that I go to college, so I’d have “something to fall back on.” I don’t think what I do specifically is important to them, as long as it’s legal, moral, and provides a living. I grew up in a blue collar family, so drawing comics didn’t always make sense as a career. Remember in the “Godfather,” when they talk about Michael being a war hero and how his father objected to him going to war but his father was also more proud of his heroism than anyone else? I think that’s probably how my people view comics. I used to talk about doing this when I was 12, so in a way I’ve achieved some goal. And they can admire that sort of goal-oriented approach. The work itself is probably a little less accessible but they are supportive.

AL: You’ve got something named True Porn listed in your credits. Spill it!

AL: You’ve got something named True Porn listed in your credits. Spill it!

JR: I’ve contributed to books called “True Porn,” “True Porn 2,” “Pornhounds,” “Fuck Farm,” “the Handy Dandy Guide to Successful Suicide,” and a Chris Reeve’s Coloring and Activity Book. When I started reading comics, they were still considered subversive or at least potentially subversive. When I started making comics, it was naturally that I’d gravitate towards those outlets, right?

AL: Can you describe anything in a comic book that ever shocked you?

JR: I don’t think so. I read “Faust” when I was 12 or 13, and that was quite a departure from “Wolverine” but I don’t remember feeling shocked. The “Little Nemo” full-size reprints were pretty awe-inspiring in ways I didn’t anticipate.

*Some images from this article were used courtesy of Jim Rugg from his public gallery.

2 Comments on Interview: Jim Rugg

Comments are closed.